Curated by Senova, Thom and the NIROX Foundation, a large-scale international exhibition programme will take place at the NIROX Sculpture Park from November 1, 2025, to April 19, 2026. The exhibition follows a modular format and unfolds across multiple venues with soft openings and closures planned throughout this period, the NIROX Sculpture Park serving as the primary venue. A full list of the participating artists can be accessed via the artists page. As part of the project several participating artists will also undertake residencies at NIROX, FARMHOUSE58, The Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture and the Kromdraai Impact Hub. Please navigate to the residences page for more information.

The Weight of Water (Hammanskraal 2023)

Alet Pretorius (ZA)

My work documents residents of Mandela Village, Hammanskraal, collecting water from a communal water tanker, a scene that speaks to years of unreliable supply, outbreaks of disease, and exploitative practices that turn water into a commodity. I want to make visible the fragile intersection between human survival and the environment. The transparency allows viewers to see through the image into the surrounding landscape, reminding us that water scarcity is never an isolated issue but one embedded in soil, ecology, and politics. Although my work is rooted in photojournalism, it anchors abstract ecological and philosophical concerns in lived realities, showing how global crises manifest in daily life. By bringing documentary evidence into dialogue with artistic research, the work highlights that soil and water are not only material concerns but also profoundly human, pressing us to imagine both responsibility and change.

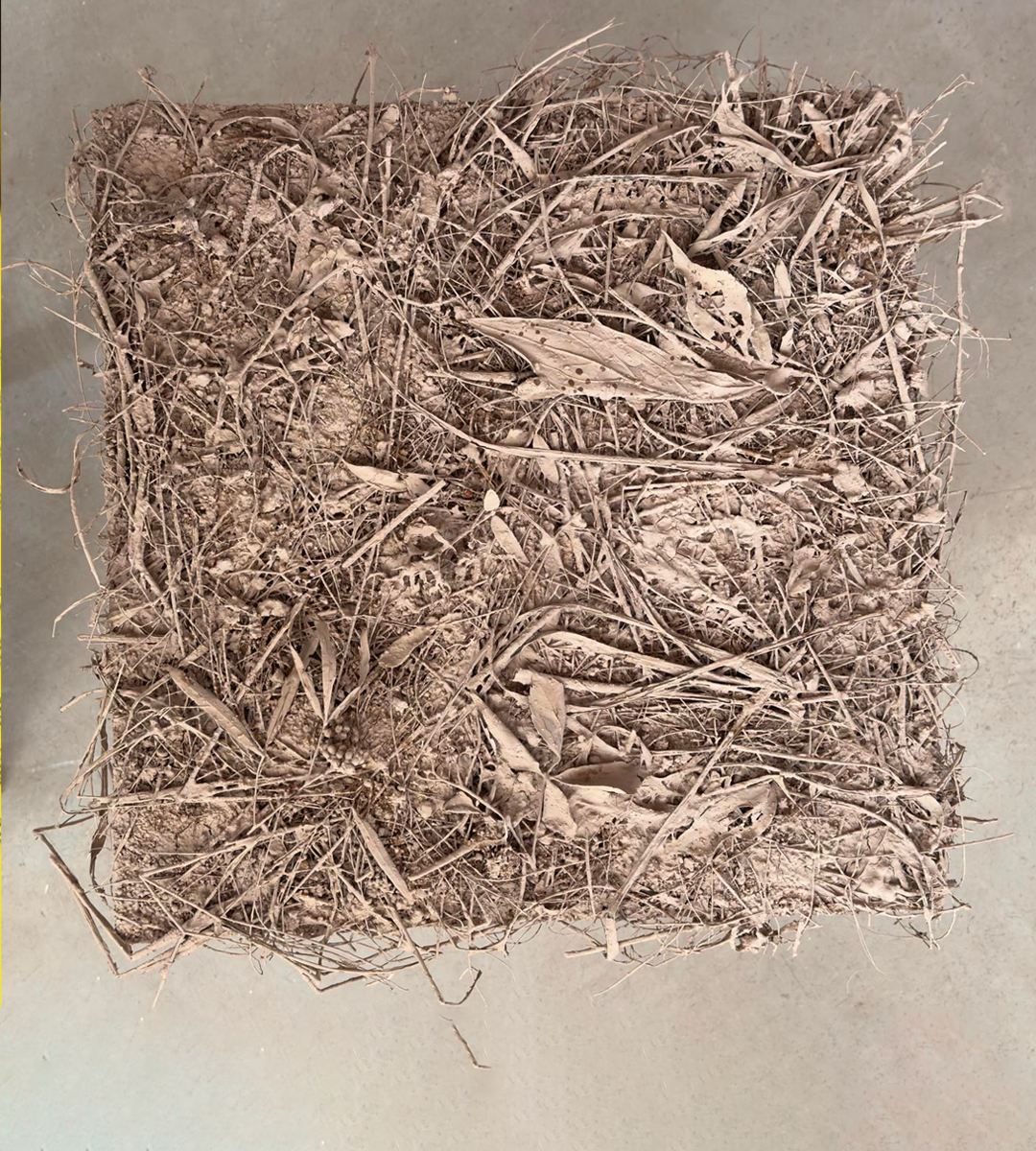

Roots # 01 - Close Reading Forms of Active Coexistence

Barbara Putz-Plecko (AT)

During a Nirox residency, as I roamed daily over the landscape, the beauty as well as the refinement and visual order of the environment suddenly aroused in me the desire to capture, step after step, its corporal physicality and the diversity of its flora and fauna. In response to research done by the Italian botanist Stefano Mancuso and to insights he provides into plants and woodlands seen as "superorganisms" that – in networks constituting perfect systems of communal use and active coexistence – cooperate and communicate with each other and are mutually supportive, I began to grapple artistically with entanglements of roots and with the question of the congruency of ecological, artistic, and social "beauty". In the process, mutualism – a form of ecological interaction that aims at ensuring the well-being of all elements concerned – became one of the leitmotivs of my observation and exploration of a physical, spiritual, and social space that is in a constant state of change. The work that I am showing within the framework of Soil and Water consists of drawings on photographs of meshes of entangled roots that I took on site, presented in relief fashion in frames of poplar wood (here, reference is made to the poplar tree and its history as "liberty tree") as well as a collage of texts taken from the thought-space that emerged in the course of my wandering through the landscape and as a result of various encounters.

Every boundary hides another

Caroline Le Méhauté (FR)

Through [Tellus Project], she is currently developing an active reflection on the restoration of degraded soils, bringing together artistic, ecological, and scientific approaches.

How to situate oneself? How to connect? How to inhabit the world differently? These questions run through her entire practice, where the artistic gesture becomes both an intimate exploration and a collective address.

Listen To Me

Christophe Fellay (CH)

Listen to Me is a bold sound installation designed as an artistic amplification of the river’s silent cry. By enlarging the groove of a vinyl record and etching it into the earth, the work transforms a collaborative sound composition—crafted from local voices and field recordings—into a monumental, visible, and tangible trace. Stretching 16 meters long, this sculpture invites the public not only to see sound but, above all, to hear the water. The project’s artistic strategy hinges on a radical reversal of traditional relationships: here, it is not humans speaking about nature, but the water itself expressing its voice through those who listen. By engaging young locals in listening workshops, recordings, and performances, Listen to Me turns the sound composition into an act of mediation between the river and its community. The phrase Listen to Me, translated into local languages, becomes an urgent call—that of the water, its currents, and its ecosystems—carried by participants and amplified through art.

The work embraces a post-dualist approach, dissolving the boundary between nature and culture by giving the water a concrete presence—not as a backdrop, but as an active participant. Collective performances, installations, and improvisations transform this call into a shared experience, where active listening becomes the foundation for a new alliance between humans and their environment. With Listen to Me, art does more than represent nature—it creates a listening situation. And voices, etched into the earth and accessible through the original vinyl and QR codes, resonate as a reminder: water is not a resource, but a living entity demanding to be heard.

Silence as a Room (I of V), Remembrance

Coral Bijoux (ZA)

The Silence as a Room, R-membrance artwork traces the echoes of human presence — how we shape and are shaped by the earth. Through acts of making, unmaking, and remembering, I explore what remains when silence meets history, and when the land itself becomes the storyteller.

We leave traces of ourselves behind — here, there, long ago (say… 10,000–195,000 years ago), and even further back, some 300,000 years.

These traces tell our story — the story of humans (and others) traversing the earth.

What remains, we gather and piece together into a version of history that defines us and shapes our identity.

Beneath the waves, across deserts, through forests, and in the mountains, Homo sapiens have endured, created, destroyed — and created again.

Folie a Deux

Diana Vives & Douglas Gimberg (CH/ZA)

The sculpture comprises a single trunk of pale blackwood acacia standing on red sandstone. Found in the Highveld above Nirox, the stone is a Black Reef quartzite formed from iron-rich sands deposited over two billion years ago. While its layered strata record compressed cycles of sedimentation and erosion, delicate layers on the oxidised outer skin evoke the movement of water long vanished from its face. This introduces to a material usually regarded as hard and inert, a certain fleshy, corporeal quality which is reprised in the smooth, sinuous surface of the acacia trunk, recalling the life of the tree over its utilitarian value as timber. Yet the way these elements are combined is far from 'natural': at midpoint, the trunk is interrupted by a diagonal cut with a traditional carpentry technique known as a scarf joint. The joint is secured by a wedge of Zambezi teak salvaged from an old railway sleeper. Ordinarily, such a joint would serve to lengthen or reinforce two pieces end-to-end. Yet our work does neither, as we have used the cut to introduce both a twist and subtle curvature to the trunk, invoking the serpentine line and contrapposto of classical sculpture — gestures that once idealized the human form. The resulting movement suggests a figure with its face turned up towards the light. To engineer the meeting point of wood and stone, the sandstone base is selectively cut and polished with manmade tools to form deliberate, assertive planes - unlike the slow, mutual adaptation of roots and rock found in nature and sometimes called root wedging or rock-tree intergrowth. This is especially sculpturally pronounced and ecologically critical in the steep topography of alpine and subalpine landscapes where seeds are arrested in the shallow crevices of rocks, germinating in a microhabitat that provides both shelter and constraint, and acts as a natural cradle in which soil, moisture and organic detritus collect. Over time, the roots conform to, and even penetrate the irregularities of the rock, effectively knitting the tree into the mountain. Creating extraordinary stability on steep slopes where erosion and gravity are constant threats, this slow, symbiotic entanglement of organic persistence and mineral resistance stands as a natural counterpoint to our intervention. However, it must be said that our intent in the mechanical joining of “earth” to “tree” to “sky” remains hopeful, if imperfect. In imitation of nature’s own integrative processes, it is an attempt at belonging - a being-with nature - enacted through artifice. It recalls the paradoxical concept of Kire in Japanese aesthetics — the “cut that connects” and through which separation becomes continuity. In this sense, the cut in Folie à Deux becomes both wound of human interference and an articulation of relation.

HOME - iKhaya

Diego Masera (AR)

HOME – ikhaya reflects on the precarious reality of millions who inhabit informal settlements—structures born of necessity, crafted from whatever materials can be found. These makeshift architectures speak to an existence shaped by impermanence and systemic socio-economic disparities.

This work seeks to confront that reality while acknowledging the profound beauty, resilience, and dignity embedded within it. The use of gold leaf evokes Johannesburg’s origins as a city founded on wealth extracted from the earth, contrasting sharply with the enduring poverty surrounding it. In doing so, the sculpture becomes a dialogue between abundance and deprivation, permanence and transience.

The title itself underscores a deeper inquiry: the distinction between a house—a physical shelter—and a home, an intimate, often fragile, construct of belonging and connection. Through HOME – ikhaya, I invite viewers to reflect on what constitutes home, to reconsider our interdependence as human beings, and to reimagine community as a shared space with one another and with nature.

The Golden Fog Collector

Ebru Kurbak (TR/AT)

The Golden Fog Collector is a large-scale golden net that captures water from fog and returns it to the pond it hangs on, exploring the entanglement of material, technology, ecology, and history. Installed in a landscape that was once the cradle of humankind, which has been scarred by gold mining and is now facing water scarcity, the installation transforms a tool driven by extraction into a gesture of restoration.

The net reflects one of the earliest human technologies: an ancient tool that extended humanity’s capacity to catch, gather and carry, providing the roots of a later-inflamed anthropocentric technological evolution. The gold threads used in the installation are sourced from traditional European manufactories that recycle gold circulating within Europe, originally extracted from various parts of the world and used in gold-decorated objects. By returning this gold to South Africa and building an unusual relationship between water and gold, the work invites reflection on the politics and enduring consequences of value assigned to materiality.

Soil and Water

Egle Oddo (IT/FI)

My motivation to create relies on long-term commitment and slow research, on direct observation and careful activation of the context. My contextual approach to the habitat, conveyed by participating in the emotional life of the ecosystem, allows an interactive connection with the living, in the perspective of an evolutionary transformation. I deploy those forces irradiating from the imagination, from the sensorial and mental identification with the forms of nature, and with its rhizomatic and chaotic processes, because I pay attention to the network of exchanges present in the environment, and its populations. Sometimes following, sometimes anticipating theoretical aspects, I have started projects focused on the relationship between persons and places in which cultural value takes on the connotations of social and political action, and the inclusion of non-human agency. Relational aesthetics has been a key to my practice. I interpret it by trans-materialising and de-materialising my artwork, shifting attention to the process and its inter-relations. In the light of contributing to form historical precedents impacting the role of the artist as relational catalyst, I am devoted to instigating life-long collective learning through art.

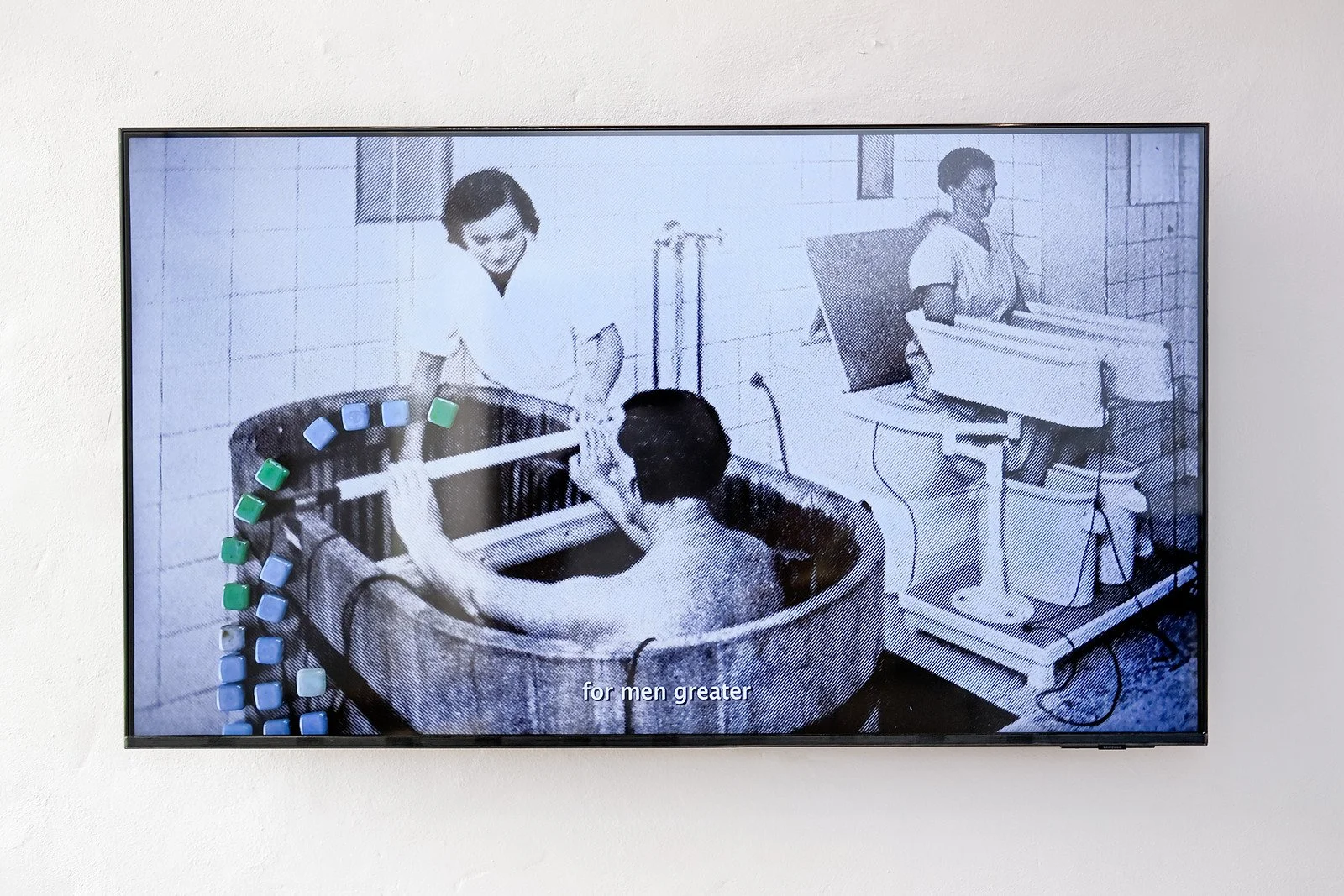

The Labyrinth of the World, Paradise of the Heart

Hera Büyüktasçiyan (TR)

In her film, The Labyrinth of the World, Paradise of the Heart (2022), Büyüktasçiyan anchors the underground and the above through the water architecture of Prague, featuring the Bubeneč wastewater treatment plant and the public baths of the city. Within the stop motion sequences, tile-like glass beads meander between the cavities of these aquatic spaces covered with glazed Rako tiles, like vocalised contours, reverberating distilled traces of cultural appropriation throughout a historical continuum. Produced in Rakovník and found across Prague, through surveying fragments of these Orientalist tiles, the artist resurfaces the underlying tensions between body and surface, ornament and power, scale and representation through constructed environments shaped around the notions of purity and cultural contamination, characteristic of Prague’s colonial past and turbulent history as a threshold of multiple temporalities and communal imaginaries.

Mudflames

Jacob van Schalkwyk (ZA)

I painted Mudflames in Johannesburg during the winter of 2025, when the days are hot and the nights long and cold. In these conditions, oil paint dries fast enough to be brave with texture. When not painting, I'd walk the streets around my studio, passing dug-up slabs of concrete sidewalk or drilled out sections of tarred road – surfaces in the way of accessing a pipe the City needed to maintain. Some of these cavities had become flooded by clear, tranquil water. More often than not, the colour of the shimmering soil they revealed under the tar was similar to the ritual clay I use in my studio, where I combine it with cold wax medium and resin to make an oil paint I can fully respond to. Just like I did outside with the red Johannesburg soil, I found myself enchanted by the grit, the flow and the drying patterns of my ritual clay paint in the studio. Mudflames is a good example of this work, which I did so I could get closer to painting what I see with my eyes closed.

Llano

Jesper Just (DK)

Jesper Just’s film Llano (2012) is based on a dystopia in the abandoned town of Llano del Rio, plagued by water supply troubles. The arid setting overlaps with the hysterical behaviour of a woman performing compulsive actions accompanied by artificial rain.

Llano refers to the ruins of a place that no longer exists but also to a place that never happened. There is a double meaning: a strange mixture of utopia and dystopia, filled with failure and potent ideals. Llano (2012) is set in the remains of the town Llano del Rio, which was founded in 1913 in California by the socialist Job Harriman. As a result of a failure to irrigate the fields and disputes over water supplies, the project and the community were abandoned nearly one hundred years ago. To put all this into perspective and reflect upon the concept of a collapsed utopia, a set of rain bars, similar to those typically used to create artificial rain in films, were installed above the ruins.

Apart from exploring the demise of Llano del Rio, the rain also brings into play the observations on the concept of ruin made by the late German sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel in his essay The Ruin (1911). According to Simmel, architecture can be seen as a struggle between man and nature, with man empowering the latter.

Once human-made structures begin to disintegrate, it is precisely from the impact of nature that new and different forms and materials evolve. The ruin, in other words, represents a second encounter between humanity and the forces of nature. As rain permeates the ruin, gradually causing it to break down, the site transforms into an even more ruinous structure.

In the film, the desert and the remnants of the utopian city are visible in the pouring rain. Soon, the camera reveals a set of pipes mounted over the ruins. At the centre of it all, a woman struggles to prevent the collapse from occurring.

Like Sisyphus pushing his rock, she continuously replaces the bricks and stones that fall from the already dilapidated structure. Meanwhile, the camera repeatedly takes us to a dark and gloomy engine room that seems to be connected to the ruin in some indefinable way.

Antecedent Wayfinder

Jessica Ostrowicz (UK)

My practice investigates the concept of home, understood not as a fixed or singular entity but as a shifting condition shaped by memory, longing, and displacement. Home often emerges in subtle gestures and overlooked details: the fold of a tablecloth, the scent of wax, or the imperfect closure of a drawer. For those who are uprooted, exiled, or confined, home becomes a paradox: at once a source of orientation and a haunting absence. Through my work, I collect and assemble fragments that gesture toward this ambiguity. Found and discarded materials — scraps of paper, architectural remnants, small objects encountered in everyday movement — are reconfigured into drawings, objects, and installations. These are often layered with sound, extending the work into spaces of resonance and memory.

My installations occupy the threshold between belonging and not belonging. They examine the distance between idealised cultural images of home and the instability of lived experience. By engaging with material fragility and processes of accumulation, the work reflects on how meaning is inscribed in the spaces and objects that surround us, and how these, in turn, shape personal and collective identity.

Ultimately, the practice seeks to reconcile contradiction: the desire for stability with the inevitability of rupture, the familiarity of home with its potential for estrangement. The resulting works, whether installation, object, or gesture, offer moments of reflection in which fragments are temporarily gathered into something whole. They invite the possibility, however fleeting, of experiencing home, or at least the trace it leaves behind.

LH#1 (left heel - the weight of my body in clay)

Johan Thom (ZA)

This process-based artwork was made by repeatedly printing my left heel in small balls of raw porcelain clay and firing the resulting objects. The work is made to the current weight of my body.

The artwork is an ode to the lowly heel, a vital part of the body we rarely think about. But, as we no longer walk toe first, modern humans constantly carry the full force of their weight on their heels.

The artwork is an accompanying piece to RH#1 (right heel - the weight of my body in clay) made in 2024, and held in the permanent collection of Foundation Casa Wabi, Mexico - over 14,000 kilometres away. In recognition of my complex heritage as part of the Dutch and European colonial settlers, I chose to render my left heel in white porcelain clay. In this sense the work also traces my journey through different parts of the world, making visible a small part of my impact and continued presence thereupon.

Undulation III

Ledelle Moe (ZA)

Undulation III is a continuation of core thematics in my work including concepts of monumentality, fragments, and ruins. Created from soil, cement, water and steel, this inchoate form oscillates between recognizable imagery and an inert, amorphous monumental mass, grappling with notions of permanence and impermanence, strength and vulnerability.

“The Latin word "humus" means "earth" or "ground," and is the root of the word "human". This connection highlights the idea that humans are fundamentally connected to the earth, both in origin and in our physical makeup, as we are composed of elements found in the soil and ultimately return to the earth. The term "humus" also refers to a component of soil, specifically the dark, organic matter formed from decaying plant and animal matter”.

Working with local materials—sand, water, soil, cement, and steel—I reflect on the material complexities embedded in this work. Concrete presents a paradox: it provides essential solutions for our built environment while simultaneously creating problems for the natural world. Ubiquitous and impervious, it resists breakdown. This tension between the built and natural worlds represents a precarious balance I seek to embrace in this work.

The processes involved with making this work are slow and arduous. Hand made by myself, these industrial materials are harsh and resistant. At the same time, they require gentle nuances and lend themselves to elastic and malleable forms. Bringing sand, water and cement together is an intimate process for me. This work is an autobiographical narrative about my tenuous, fragile relationship with the desire for solidity and permanence and the acknowledgment of the impermanent, unfixed and temporal quality of all things.

Orphaned Tears

Lundahl & Seitl (SE)

Lundahl & Seitl are partners in love and in art whose relational practice reimagines the exhibition as an embodied score. Through choreography, sound, voice, and language, they make the visitor’s own perception and movement the material of the artwork, creating temporal experiences to be passed through rather than looked at. Their works dwell in the interval between material and immaterial form — salt crystallisations of tears, shafts of refracted light, mist, sub-bass resonance, and scent particles: memory made molecular. Their current long-term project, River Biographies, evolves as a living archive shaped by rivers and their communities, refracting ecological, emotional, and cultural memory into site-sensitive constellations of bodies, waters, and stones.

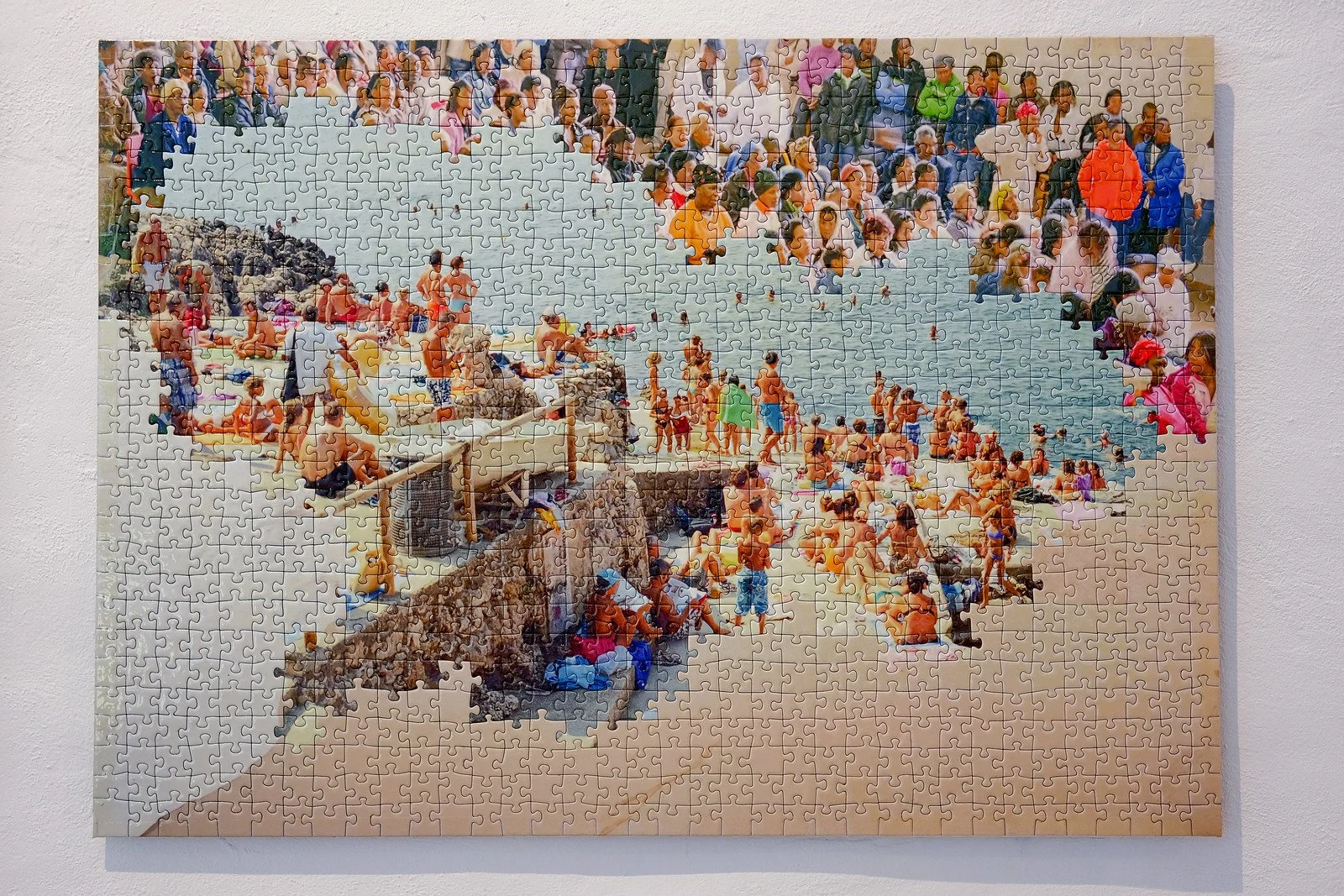

The sea. What separates us, holds us together

Maria Lantz (SE)

“The sea” has been a theme in Maria Lantz artistic works along with her interest in global economy, urban life and informal relations. In her recent project, she has ordered jigsaw puzzles from some of her images. The pieces are put together but mixed between the puzzles. Here, new images appear in this mosaic-like collage method.

The art works evoke thoughts on how we are split up in the world, but also how we are connected and how we relate to each other.

The sea separates us – and holds us together.

Quiet Water Quiet Soil

Marcus Neustetter (AT/ZA)

A drawn meditation on water and soil. Over the past decade, Neustetter has explored the spaces above and below the landscape, where the earth breathes air and water through its portal-like caves, volcanoes, subterranean rivers, and natural wells.

In 2025, upon returning to the Cradle of Humankind with camera, paper, and drawing tools in hand, the artist set out alone in search of ways to capture a fleeting trace of this seemingly timeless breath. Through marks, forms, film, and image, he attempts to connect with that which is greater, smaller, and ultimately beyond understanding.

This gesture finds resonance in his abstract studio dialogue with musicians Anathi Conjwa and Micca Manganye, together seeking to give voice to our fragile tether to the earth.

Plasticised Trees

Paula Anta (SP)

Paula Anta's 'Plasticised Trees' respond to the overwhelming presence of plastic in our environment. Made largely from fossil fuels, plastic fuels climate change and infiltrates ecosystems.

Paula wraps fallen trees in discarded plastic bags, heat-bonding the material to the bark to create a second skin that is at once protective and confronting.

Referencing Europe’s waste-sorting colour codes and the corporate branding saturating South Africa, these works stand as evidence rather than debris, suggesting how the remnants of environmental harm might also contribute to repair.